Witnesses saw him marching forward with a young child's wrist in his hand, followed by the entire phalanx of his beloved orphans, dressed in their best costumes as if for an outing in the countryside.

Photo by Adrian Grycuk - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 pl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62908535

Overview

Henryk Goldszmit was a world-famous Polish-Jewish author of more than 20 children’s books, a renowned teacher and educator whose reputation was known throughout Europe and beyond. He was often called Pan Doktor (Mr. Doctor) or Stary Doktor (Old Doctor).

Yad Vashem in Israel is the famous memorial to holocaust victims and one is overwhelmed by the multitude of people from different parts of the world the Nazis gathered and killed mercilessly. There is a connection with this memorial with Henryk, a man from Poland.

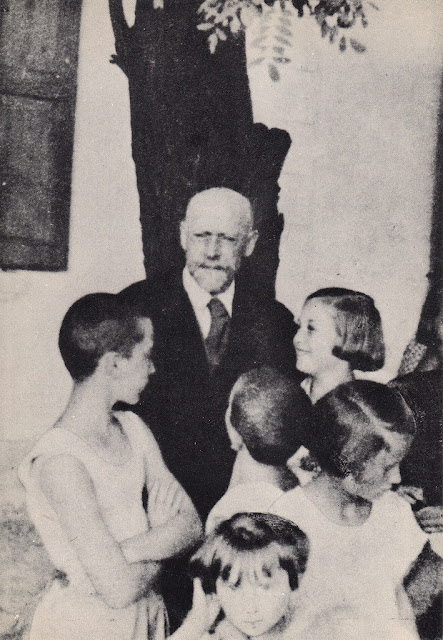

Henryk with his loved children

Henryk's Belief

Henryk was an extraordinarily gifted man. A scholar and writer, he was also a doctor and a human rights activist, especially an ardent children's rights advocate. In fact, children represented the very core of his passion. Though he went on to write more than twenty books and a thousand articles, his very first book questioned the way most parents rear their children.

At a time when corporal punishment was acceptable for parents to inflict upon disobedient children, Korczak’s 1925 masterpiece, “The Child’s Right to Respect”, was published, read in many countries in translation from the original Polish, and for this unique book Janusz Korczak was awarded a literary prize.

He believed, for instance, that for a father to foist his religion on his child, instead of letting him or her faith later when he or she turns an adult, was nothing short of ruinous brainwashing.

He studied medicine and became a pedestrian in a children's hospital in Warsaw. At the same time he wrote for several Polish publications and gained a literary reputation for his adopted pen name Janusz Korczak. For a while he served as a military doctor and studied in Germany but eventually veered to head an orphanage for Jewish children. He invited a close friend Stefania Wilczyńska , to be his assistant and set about creating a new kind of instruction for children.

Photo by Nieznany/unknown - Maria Falkowska, Kalendarz życia, działalności i twórczości Janusza Korczaka, "Nasza Księgarnia", Warszawa 1989, Domena publiczna, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26777496

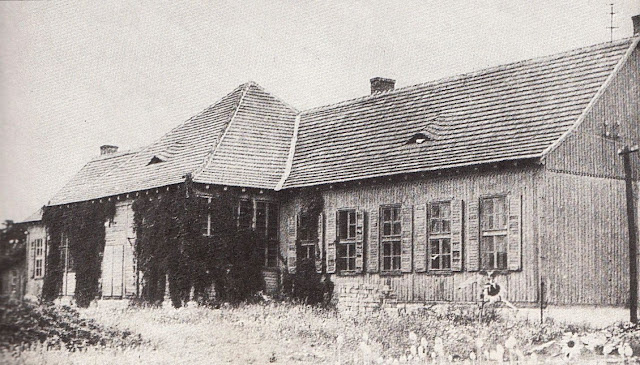

Henryk's orphanage Dom Sierot, was a children's republic, run entirely on democratic principles, where all decisions were collectively made through its parliament and court. Henryk even hired a novelist, Igor Newerly, as a secretary to help the orphans produce their newspaper. Which came out as a supplement to a Warsaw newspaper.Maly Przeglad (Small Review) and it was attached to the week-end edition of Poland’s largest Jewish daily newspaper, printed in Polish, Nasz Przeglad (Our Review) read by thousands of Polish Jews every day.

The orphanage under Henryk's guidance became an independent small country all for the children.

Photo by Anonymous - http://fcit.usf.edu/HOLOCAUST/KORCZAK/photos/naszdom/default.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4788925

In 1933 the Polish government bestowed upon him the Silver Cross of Polonia Restituta, (Reborn Poland).

Each year from 1934-1936 he traveled to Palestine and was immensely impressed with the kibbutzim and, in particular, with the special care given to young children following the ideas of which he had written.

In 1936 he was invited to move to Palestine either to practice pediatric medicine or to be a professor in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. But Dr. Korczak refused the offer because he would not abandon the children in his orphanage.

All hell broke loose on 1st September 1939, as Hitler invaded Poland with thousands of planes and tanks. World War ll had begun. Within months the Gestapo created a small area as the Warsaw Ghetto and forced all Jews to move there. Henryk was compelled to move to a smaller building in the Ghetto with all about 192 (ot 196) children and 12 supporting staff including Henryk and Stephania

The Ghetto Warsaw

Britannica.com states that

As part of Adolf Hitler’s “final solution” for ridding Europe of Jews, the Nazis established ghettos in areas under German control to confine Jews until they could be executed. The Warsaw ghetto, enclosed at first with barbed wire but later with a brick wall 10 feet (3 metres) high and 11 miles (18 km) long, comprised the old Jewish quarter of Warsaw. The Nazis herded Jews from surrounding areas into this district until by the summer of 1942 nearly 500,000 of them lived within its 840 acres (340 hectares); many had no housing at all, and those who did were crowded in at about nine people per room. Starvation and disease (especially typhus) killed thousands each month.

Beginning July 22, 1942, transfers to the death camp at Treblinka began at a rate of more than 5,000 Jews per day. Between July and September 1942, the Nazis shipped about 265,000 Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka. Only some 55,000 remained in the ghetto. As the deportations continued, despair gave way to a determination to resist. A newly formed group, the Jewish Fighting Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa; ŻOB), slowly took effective control of the ghetto.

|

The Irony and His Attachment

The tragic irony was that

Henryk himself was a skeptic, and didn't believe in Judaism. He had

numerous opportunities to leave Poland before the German onslaught, just as his assistant Stephania had departed for Israel. But Henryk didn't

want to go anywhere where he could not also take his children.

Now,

with his children, he was cornered in the Ghetto, from which there were

weekly shipments of people to the murderous death camps, gearing up

their killing apparatus. Henryk knew his turn and the turn of his

children would soon come. How could he prepare them? What message could

he give children ranging from 3 to 13?

It was then that he

took an astounding decision. He was abreast of European literature and

the Nobel Prize probably brought Rabindranath Tagore's name to his

attention. He decided that his children would stage Rabindranath's play,

The Post Office, whose central character was an ill child AMAL,

surrounded by other children, who struggles to fashion a world of his

own.

|

| Rabindranath Tagore |

The Post Office (Dak Ghar in Bengali)

In Act II Amal’s physical condition deteriorate. None sees any hope of his survival. Headman mocks him giving him a blank letter. But at last the king’s Herald and the King’s Physician come. Lastly Amal dies. Thus the play deals with Amal’s tragic story of suffering and pain on the surface level. But a deeper analysis will reveal that Amal’s death is not at all a tragic one. Instead it is seen as union between human soul and the Supreme Being. Amal is an innocent boy who is tired of the suffering of his life. Therefore he is eager for deliverance from this earthly existence. It is an invitation to leave this world of pain and suffering and enter the world of eternal bliss. At the end of the play Amal says to the State’s Physician: “I feel very well, Doctor, very well. All pain is gone. How fresh and open! I can see all the stars now twinkling from the other side of the dark.”

|

Image from the short film DAK GHAR- BY Zul Vellani (1965) Part II |

Each character, like Amal, has a significant role to play in the inner drama of the soul waiting for deliverance. Watchman symbolizes time. That time is most powerful and wants for none is clearly stated by him: “Watchman: My gong sounds to tell people, Time waits for none but goes on forever.” Thus behind the apparent simplicity of the dialogue, deeper and profound meaning continues to flicker. Sudha who gathers flowers stands for sweetness and grace. Madhav solicits like a common man of prosperity. The Physician symbolizes bookish knowledge that prevents man to achieve wisdom and true knowledge. Even the wicked village Headman has his place in the rich drama of life standing for his place in the rich drama of life standing for his obtrusive authority. Amal alone is an angelic creature, apparently passive but highly creative through his imaginative perception. The play is a series of dialogue but each dialogue vibrates with meaning.

You can watch the film Dak Ghar here >

W.B. Yeats was the first person to produce an English-language version of the play; he also wrote a preface to it. It was performed in English for the first time in 1913 by the Irish Theatre in London with Tagore himself in the attendance. The Bengali original was staged in Calcutta in 1917. It had a successful run in Germany with 105 performances and its themes of liberation from captivity and zest for life resonated in its performances in concentration camps where it was staged during World War II. Juan Ramón Jiménez translated it into Spanish; it was translated into French by André Gide and read on the radio the night before Paris fell to the Nazis. A Polish version was performed under the supervision of Janusz Korczak in the Warsaw ghetto.

In late July in front of the Ghetto denizens with

whatever limited resources they could lay hands on, Henryk's children

staged a scintillating performance of The Post Office.

Nine days later German transport came to take them to the Treblinka death camp.

Report

suggests that the German were prepared to let Henryk go or to send him

to a less harsh camp. He would not hear of it. He would not part from

the orphans. Witnesses saw him marching forward with a young child's

wrist in his hand, followed by the entire phalanx of his beloved

orphans, dressed in their best costumes as if for an outing in the

countryside. To the horrific end, Henryk stood with his beloved

children, unbowed. Janusz Korczak had written his last and best novel

with his life.

Final Thought

One hopes - as any discerning reader

of The Post Office (Dakghar) hopes -- that the play gave them all a

message of solace the undimmed speck of assistance that lies in an

indomitable Spirit be it even on an ailing child Amal.

Probably Henryk thought -that address death as a form of freedom. First and foremost, when the Watchman and Amal obliquely discuss mortality, the Watchman describes time as going onwards, and though no one no knows where it is going, everyone will go there one day. The Watchman also says that perhaps

one day the doctor will hold your hand and take you there.

When Amal says that the doctor doesn't let him go anywhere, the Watchman replies that he is referring to a greater doctor, one who can set you free. In other instances, as Amal is dying, he says that he feels better, that he feels no pain. At the very least, then, death can be seen as freedom from the body and its constraints. Some of Amal's final words also indicate that death is a beginning and not an ending; he says,

Now everything is open—I can see all the stars, shining on the far side of darkness.

This psychological paraphrase was probably implanted into the minds of little orphans so well, it is reported that none of them cried or tried to flee when they marched into the Gas Chamber.

A Documentary on Janusz Korczak, the pen name of Henryk Goldszmit is here

And a lecture by Dr. Henry Abramson based on research of Janusz Korczak's life >

Related Posts in this blog

|

Wisdom - the quality of being Wise |

|

The Vocabulary of Emotions |

|

How to Conquer Math Anxiety |

I just read an article in the Times of Israel by Jak Jeffay about Stefania. I then checked some more research papers. I have now no doubt that Stefania is largely overlooked and ignored in the history of killing of orphans by the Nazis.

ReplyDeleteI strike through the line in the blog intentionally instead of deleting the line to notify the mistake in the lines of history books.

I sincerely hope that I will find some more information on Stefania's life and work and will be able to publish an article on her very shortly.